LAESTADIUS BOTANIC GARDEN AT KARESUANDO

A Forsaken Garden

Visited June 24th, 2016

Leaving Jokkmokk on Friday afternoon we drove four hours northeast to reach Karesuando, the northern-most church village in Sweden. It is located on the Muonio River which runs 324 miles (522 kilometers) long forming a natural border between northern Finland and Sweden. Our destination in Sweden shares it's namesake with the Finnish village on the other side of the river. Karesuando,with a combined head count of barely 500 on both sides of the river and Kiruna, the nearest town over one hundred miles away, would in all appearance be an unusual place for George to pin-point this spot to travel those hours and miles.

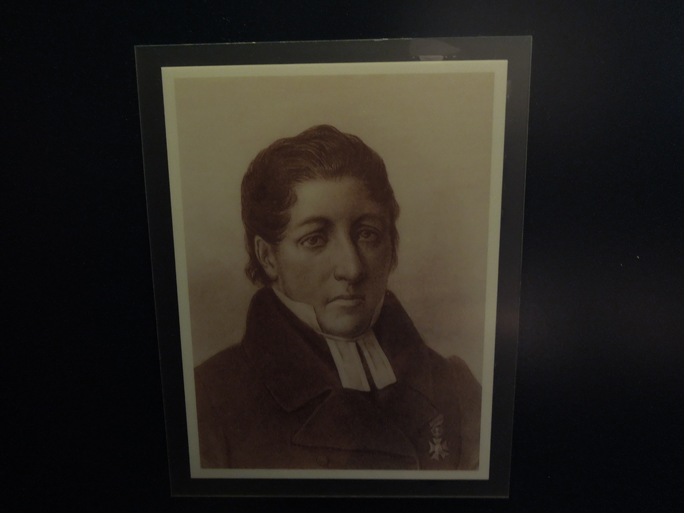

Karesuando is important to the Sami though; 150 miles (250km) north from the Arctic Circle it is located half way between two traditional reindeer grazing areas. A rest stop for the reindeer herder, it is the center of the Arctic Region. In the mid-1800's it became the center of a Lutheran revivalist movement driven by a Swedish Lutheran priest ministering to the Sami people, Lars Levi Laestadius (1800-1861), who was also botanist. For George it was a calculated reason for our destination; to visit the botanic garden at Karesuando in Lars Levi Laestadius name and memory.

Lars Levi Laestadius was born January 10th, 1800 in the Swedish Lapland village of Jäkkvik. His mother was Swedish Sami and his father a Swede. The family lived in poverty as his father was an alcoholic and could not keep employment. When Lars was eight years old, his family went to live with his half brother Carl, a Lutheran pastor in Kvikkjokk. Carl was also an amateur botanist and had traveled with the well known botanist, geographer and geologist, Göran Wahlenberg, on an excursion in the Kvikkjokk area. Carl encouraged Lar's interest in botany starting with summer holidays learning about and collecting the flora around Kvikkjokk. Carl provided for Lars and his brother's early education until his death in 1817.

During his secondary education years Lars self studied botany as it was not in the schools curriculum. He took his first botanical excursion across the Scandinavian peninsula to Helgoland, on the coast of Norway at age nineteen. His travels for three months, often alone on foot in the wilderness, have been compared to Linnaeus and Wahlenberg botanical travels. His report of the journey was published and so impressed the Swedish Academy of Science and Letters that they underwrote his future excursions.

At twenty years of age Lars entered Upsala University where he studied botany under Göran Wahlenberg, who occupied the university chair previously held by Carl Linnaeus. Lars showed himself to be a brilliant student and was made assistant in the botany department while also pursing his studies in theology. Several of Lars later botanical expeditions on behalf of the Swedish Academy of Science were due to Wahlenberg's recommendations. In the summer of 1822 he traveled with Wahlenberg to Skåne to study and draw Scandinavian plants to be used in Sweden's botanical scientific work. Friendship and correspondence between the two continued until Wahlenberg's death in 1851.

After being ordained a Lutheran priest and the vicar in the Karesuando parish, Lars married in 1827, a local Sami women Brita Alstadius, who had been his childhood friend. Together they had fifteen children, with three children dying young. From 1825 to 1849 he served as a clergyman in Karesuando where he taught the people and promoted sobriety among the Sami.

He continued his interest in natural history and science while ministering to his congregation and traveling to all of the Sami parishes in Sweden Lapland. On a summertime trip to a parish on coast of northern Norway in 1831 he found a special poppy that was later named Papaver laestadianum. His other important discovery was the Norway plant Saxifraga paniculata. On these trips he collected thousands of plants from Lapland and Norway. He exchanged a variety of plants for southern species to compare with the northern Lapland plants.

The French Navy requested his services as a field guide in the La Recherche Expeditions due to his knowledge of botany, the Sami people and their languages. In 1838 that travel was to the Norwegian Atlantic islands, the Faroes, Iceland and Spitzbergen plus the interior of Northern Norway and Sweden. He wrote of the plant life in the high arctic and noted his meteorological observations. The culture of the Sami people, (as well as the ancient Sami), their folk beliefs and legends he collectively called a mythology. His writings of the Sami at that time were important as their traditional religious beliefs were passing into history due to the Church of Sweden's Christianization of the Sami people.

It was the leader of the expedition, Joseph Paul Gaimard, who held Laestadius's final work, “Fragments of Lappish Mythology,” in his private collection until his death in 1858. The two part manuscript then disappeared until part one was rediscovered in 1933 in the Pontarlier library in France. In 1946 part two was unexpectedly discovered in the manuscript archives of Yale University. The manuscript was published fully in Swedish in 1997 and translated into English in 2002.

For Lars Laestadius's participation in the La Recherche Expedition, he was awarded the Medal of Honor of the Legion of Honor of France. He was the first Scandinavian to receive this honor. The French Academy received 6,500 plants in his herbarium. After his death, his surviving herbarium of approximately 6,000 plants was purchased by the Swedish Museum of the Riks in Stockholm. The numbers indicate his proficiency of plant discoveries and collections during his lifetime which he meticulously documented.

In his time, Lars Laestadius was an internationally recognized botanist and a member of the Edinburgh Botanical Society and the Royal Society of Sciences in Uppsala. He was acknowledged as an authority of arctic flora. He was an author who wrote in the languages of Latin, Swedish, Finnish and Sami. At age twenty, before entering the University, he had successfully experimented with his parents potato crops to increase size and yield. By the age of twenty-four he had written a small book on the crops in Lapland based on his knowledge of climate and the soil of northern Sweden. He believed that it was possible to become almost self sufficient with the agriculture products in Sweden. He pushed for potato cultivation as well as cultivating suitable soil for grain crops and cultivation of land for pastures.

At age thirty-nine he was writing that the soil, climate, and most importantly light, have a major impact on the color, intensity and lushness of the flowers in the north. He wrote that climate and soil conditions can significantly modify plants. Several Nordic species he did consider modifications. He also wrote of his observations of the relationship of plants to their geographical environment. In 1839, those views were questionable but now his observation are an important part of botany.

His place in the history of botanical geniuses ( once called the successor to Carl Linnaeus), and one of the early pioneers in the exploration of plant life in northern Scandinavian, may have been overshadowed due to his parish visit on New Years Day, 1844 in Lapland. Following his sermon he had a visit with a poor abused Sami women known in the church as Mary of Lapland. Mary belonged to a Lutheran revival movement that emphasized Biblical doctrine, individual piety and living a zealous Christian life. Levi Laestadius had a personal spiritual conversion after his visit with Mary, entering a state of grace and receiving God's forgiveness for his sins. He said that he understood the secret of living faith and he saw the path that leads to eternal life.

He returned to his parish in Karesuando preaching a strict moral code including absence from alcohol, forsaking vile language, greed, vanity, worldly joy and anger. He preached against the priest and traders who became rich at the expense of the Sami. He wrote protests against the spiritually dead doctrines taught by the traditional church. He preached of a God who cared about people and their lives. He successfully related his message (preaching in Sami dialects) of repentance and confession of sins using metaphors from the Sami lives that they would understand. There was crying with the emotion of confession of sins, and ecstasy while praying for forgiveness within the congregation. The Sami who had summer reindeer pastures in Norway and winter pastures in Sweden, contributed to the spread of the strict conservative Christian religion which created one of the biggest revivalist movements (a return to Martin Luther) in the Nordic countries and in 1853, a split from the Church of Sweden. Laestadianism also spread across the Atlantic Ocean. In the United States the groups are under the name Laestadian Lutheran Church and the Old Apostolic Lutheran Church.

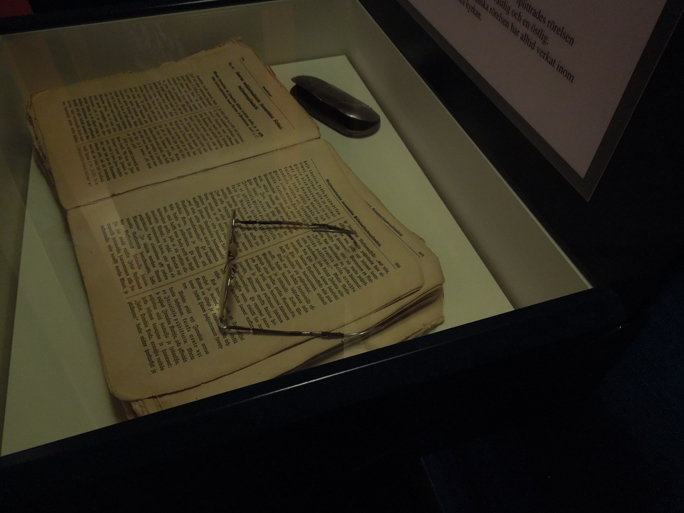

There was less time for botany with time now spent on his duties of the revivalist movement and a move to Pajala in 1849. His interest in botany did continue though with articles written and correspondence with botanist from Sweden and other countries. Towards the end of his life he experienced “impending blindness,” and had contracted a cholera-like illness. Less than a year before his death on February 21st, 1861, he sent a letter and a pack of plants to Nils J. Andersson in Stockholm with a request for pressed plants to be sent back to him for comparison and examination. He was still the inquisitive botanist.

It was early afternoon when we reached the cabin campground at Karesuando. Not being sure exactly where the memorial garden for Lars Laestadius was located, we stopped at the small eatery on the campgrounds.

It was a public holiday since it was Midsummer Eve and children were outside playing so we were able to have a quiet visit with the owner of the campground. While we ate pastries with our tea and coffee, she told us that she had bought the campsite three years ago. She did not have the time to take care of the memorial garden and thought it had been abandoned for numerous years.

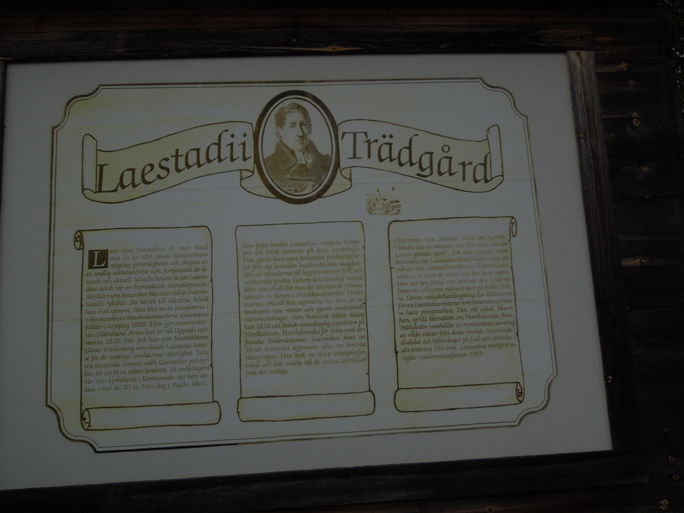

With directions we were able to locate the garden on the campground. A sign on a wooden fence with the faded portrait of Lars Levis Laestadius marked the entrance to the garden which had been established in 1989.

The grass was neatly mowed around the perimeter of a mounded garden with the border defined by small boulders. A few arctic plants were in bloom.

The alpine catchfly (silene dioica), which can grow in nutrient poor mountain rocky soil, was poking it's fragrant reddish pink flowers above the tall wood horsetail grass that overpowered any of the shorter alpines that might have been there. Surprisingly, the writing on the plant labels were still visible.

If the Papaver laestadianom once planted in Laestadius's honor was still in the garden and in bloom, we could not tell. Chances were that it still was there; a tenacious survivor of arctic plants that do not need our intervention to renew their life cycle. Now, it would take a keen botanist's hands and eyes to rejuvenate this remote and forsaken memorial garden for Lars Levi Laestadius.

CREDITS

Photos by Deborah Ellen McMillin

“Botanist Lars Levi Laestadius” Alfred Granmo (University Library Tromsø series)

“Fragments of Lappish Mythology,” Edited by Juha Pentikäinen (from Wikipedia)

“Laestadius, Lars Levi.” Encyclopedia of Religion. Encyclopedia.com

“Lars Levi Laestadius,” Swedish biographical dictionary by Olle Franzén

https://www.laits.utexas.edu/sami/diehtu/siida/christian/laest.htm

TRAVEL REFLECTIONS

A reflection of our journey for fellow travelers with photographs that Roy and I took during our first week starting in Trondheim, Norway where we met. Lennie and I flew in from the States meeting George, Roy, Dorothy, Norah, and Roy who flew in from Manchester, England.

We won't forget our major form of land transportation; the seven seat Ford rental car reserved for us that was smaller than expected. An attempt for a larger vehicle for the duration of the trip with the car rental company at Trondheim, was unsuccessful. Once Roy, (who took this photo at the lunch stop in Moskosel, Sweden) figured out the luggage placement, preferences for seating were settled; Roy in the drivers seat with George (and the GPS) as navigators. With Norah, Dorothy and I in the middle back seat and Lennie's choice of the far rear sixth seat surrounded by luggage, we managed amicably for the duration of the trip.

We left Trondheim Wednesday morning. This side of Norway is warmed by the Gulf Stream. Farms were in the valley and on the low hillsides. Bulging white silage bags dotted the lush green pastures. The majority of the homes painted in the transitional Nordic colors of golden yellow and deep sienna red. In Trondheim the mountains were lush with conifers that capped the top of the peaks green. I would observe the mountain landscape gradually change as we continued our travels away from the coast northward.

Scenic forested route on the morning drive to Hemavan. According to the road sign there is only one direction from which to choose from.

After our visit to the Botanical Garden of Hemavan on Wednesday afternoon, we traveled a short distance to the Tärnaby Fjällhotell that overlooks Lake Gäutan. Heavy forests were on each side of the pristine lake. Distant mountaintops bare of timber growth showed patches of remaining winter snow. This scene was reflected in the placid lake's water where the dim evening light would linger until early morning. I took an evening photo while on a night time walk and Roy took a morning photo.

On our way from Hemavan to Jokkmokk on Thursday morning, Roy decided to slow down to take a photo from the drivers window. It was his excuse to give this pair of antlers the right of way.

Early afternoon we reached the Arctic Circle which is defined as the southernmost latitude where the midnight sun can been seen at the summer solstice. Its position is defined by the inclination of the earth's axis which varies under the influence of the sun, the moon and the planets. Norah, Lennie and I posed for an Arctic Stone Circle photo.

A souvenir shop was at the top of a hillside with a view of the lake and forests on the other side of the roadway. Roy and George let us ladies do the climbing up the steps to check out the arctic trinkets. We were six miles (10 km) from Jokkmokk, our destination for the Alpine Botanical Garden and Ájtte Museum.

At the Arctic Circle the alpine lady's mantle, common in the mountainous regions on lime deficient soil, growing with a companion plant, the alpine catchfly with reddish pink flowers.

On Friday (June 24th) we left Jokkmokk after our morning visit to the botanical garden traveling northeast to Karesuando. We stopped for a noon lunch at Lappeasuando Hotell Cafe not far from Gällivare, Sweden. The cafe specialized in local fare of moose, reindeer and fish. Several lunch stops were made on the trip at small cafes that served regional fresh foods. A change in diets for us.

The Muonio River that divides Sweden and Finland runs through Karesuando. We did a cross over into Finland across the bridge that divides the two countries. It was a short distance from the river to Lars Levi Laestadius's garden.

Friday we had a stop over for the night in the Arctic Highlands of Northern Norway at Kautokeino, the traditional winter base for the Norwegian Sami and their reindeer. On our visit the town was quiet, as the reindeer were out to summer pasture. However, in the wintertime there are approximately 10,000 reindeer in the area. The majority of the residents speak Sami as their first language. Roy snapped a photo of a Sami goahti in Kautokeino and a panoramic view of the Kautokeino scenery from the Thon Hotel balcony.

On Saturday morning at Dorothy's suggestion, we visited the Juhls' Silver Gallery in Kautokeino. The best of Scandinavian jewelry design in traditional Sami silver and modern design can be found in their unique show rooms. Dorothy was wearing a silver pendant that day that she had purchased at the gallery years earlier. I chose a silver pendant and matching earrings of the reindeer design; a long lasting reminder of our four legged hoofed companions on the Sweden roadway.

We then headed to Tromsø; eight hours of highway miles. We were not a group to stop for scenic photos along the roadway; difficult and dangerous on curving mountainous two lanes. This water cascade was a car stopper for Roy though. He pulled over, jumped out of the car and snapped this quick photo. I took the opportunity to snap my own photo also.

.

On the occasion when the pavement reached an end, an alternative form of transportation was employed. Two ferry crossings; from Olderdalen to Lyngseidet and then driving the highway to catch the next ferry timed for Svensy to Breivikeidet. It gave us a chance to see from a different perspective the dramatic views of the fjords and mountains in northern Norway. It gave Roy a chance to get out from behind the wheel and click these travel shots.

I caught a glimpse of Santa Claus coming out of the woods as we were pulling in to dock from our ferry crossing. He was on a Norwegian summer camping vacation from the North Pole with Mrs. Claus enjoying the warm long daylight hours. He may have been picking mushrooms in the woods for vegan vegetable potato stew (no reindeer in Claus's stew), and chokeberries from the bushes for Mrs. Claus to make a tart jam for soft heart shaped breakfast waffles.

By early evening we had reached our northerly destination; Tromsø named “Gateway to the Arctic ” in the late 1800's. We were 214 miles (344 km) from the Arctic Circle and 1408 miles (2265 km) from the North Pole. History can be found in Tromsø as the center of seal hunting in Northern Norway. Later it was as a base where the most successful Polar expeditions were led by the Danes and Norwegians who learned useful skills from the natives. In the early 20th century (to name a few), Ronald Amundsen, Fridtjof Nansen and Umberto Nobile departed from Tromsø on their perilous and at times fateful journeys which are now legendary.

Over five days and a thousand plus miles we had driven through Sweden's dense spruce and pine Lapland forests and mountains to reach Norway's Lapland. Here atop the summit of Storsteinen peak overlooking the town, arctic winds buffet the few scattered dwarf trees and ground hugging, tenacious alpines that have adapted to the harsh climate on the sparse rocky slopes.

Tomorrow we will visit the Tromsø Arctic- Alpine Botanical Garden where the climate is favorable for plants from the polar region and the high mountains to flourish in a beautifully maintained garden for the traveling garden enthusiasts enjoyment.