Visited on September 7, 2009

David and I visited Kew Gardens in September 2009, which coincided with the 250th anniversary of the founding of the gardens as a botanic garden. It was 1759 when Princess Augusta, mother of King George III, started a nine-acre botanical collection of plants at Kew Palace. At that time Kew was a private country retreat for 18th century royals. In 1773 Kew Garden continued to expand when botanist and explorer Sir Joseph Banks, provided the garden with new species of plants from his expedition to the South Pacific on the HM Bark Endeavour during the years of 1768-1771. From London he continued to initiate and finance major botanical expeditions that continued plant collection around the world during the reign of King George III. His predecessor, Sir William Hooker and his son Sir Joseph, continued the tradition of collecting plants worldwide into the 19th century. That laid the foundation for Kew as it is today with 326 acres of trees, ornamentals, special gardens and glass houses with exotic and rare plants.

Our introduction to the garden was the bedding displays of plants labeled from their country or origin. The Pineapple Lily represented South Africa with long spiked flower heads rising above the white masses of the Tanzania Busy Lizzie. White Echinacea from the colder climate of North America filled in the background. Mixed with sunny colored Coreopsis, a native to the woodlands and prairies Mexico and the America’s, were coral dahlias from the mountains of South America. Sharing the stage were the tangerine blooms of Crocosmia from the grasslands of South Africa. At the back of the border the bright orange panicles of Cannas from the North and South American tropics, appeared as a sentinel over this mass of perennials and annuals. These displays represented the gathering of flora worldwide by botanical explorers from previous centuries to the present day.

The PALM HOUSE at Kew was designed to house the exotic palms being collected in early Victorian times. Many of these palms were tall, needing space for their spreading crowns. Richard Turner, a glasshouse designer and Irish boat builder, and the architect Decimus Burton, built this structure using light but strong wrought iron ship beams and glass without supporting columns. This was new technology for glass buildings in 1844 but the concept was borrowed from the shipbuilding industry. The design, an upside down ship hull, allowed the tallest growing palms to be placed in the center. The Palm House was completed in 1848 and formed a tropical rain forest habitat.

Currently the Palm House is divided into three sections with plants from the America’s and in the second section Africa, including Indian Ocean Islands. The third section exhibits plants from Asia, Australia and the Pacific, which is the region that contains the world’s greatest diversity of palms. Many of the plants native to the tropical rain forest growing in the Palm House are important economically for providing the majority of the world’s plant foods and for medicinal uses. Represented in the garden outside of the Palm House were plants for food such as ginger, taro, sunflowers, blueberries, pomegranate, pineapple, maze, and sugar cane. The use of plants for making clothing and dyes were shown in the displays of cotton, century, safflower and woad plants. For health and medicinal uses plants such as the willow, Aloe Vera, Opium Poppy and Madagascar periwinkle were also in the display.

The PRINCESS OF WALES CONSERVATORY built with 20th century technology and design, opened in July 1987 in honor of Princess Augusta. Ten different environments in one glass house represent the conditions in the tropics from desert heat with cacti, agaves and aloes, to moist tropical rainforest of orchids, water lilies, mangroves and carnivorous plants. The steeped and angled glass construction without sidewalls is designed for energy efficiency and solar collection. Since each individual environment requires its own personal climate of heat, moisture and humidity, sensors are placed in each area, which relay environmental information to a computer. The computer can then make individual changes of heat flow, the opening of roof louvers or spraying mist to increase humidity. Even rainwater from the roof slope is collected and after treatment used for irrigation. Collections of plants threatened in their native wild habitats, now under the protection of the conservation efforts of Kew Gardens are in this conservatory.

During the mid 1800’s botanical explorers were bringing back to Britain and Kew Gardens a record number of exotic plants collected worldwide. Additional space was needed to house a growing collection of semi-hardy and temperate plants at Kew Gardens. Once again Decimus Burton was commissioned to design a conservatory for these plants. Work began in 1860 but due to costs overruns and the bankruptcy of the contractor, the TEMPERATE HOUSE was not entirely completed until 1899. Due to its size it has become the home of many plants including subtropical trees and palms that have outgrown their original place at Kew. It is divided into geographical zones with plants from Africa, Australia, New Zealand, Asia and Pacific and the Americas.

The DAVIES ALPINE HOUSE opened in 2006 with 21st century design and technology. The Alpine house is designed to provide a naturally controlled environment for mountain plants that would not survive in the rain and damp winters of Southern Britain. Alpine plants require dryness but also coolness, as well as light and good ventilation. The use of low iron glass allows transparency and the high level of light that the plants need. Shade can be provided to protect from the sun’s heat in summertime with blinds that fan out and conform to the curvature of the glass structure. A complex but low alternative energy cooling system is in place. A basement chamber is used as a heat sink, cooling warm air at night before entering the glass house during the day. The arch provides height which encourages natural air movement. Openings at the top allow warm air to escape. The alpine plants are watered by hand to reduce humidity in the glass house. Surrounding the Alpine house is a rock garden with large rough boulders, water cascades and plants that represents six global regions of mountain plants from the Himalayas to the Rocky and Appalachian mountains of North America.

The Cambridge Cottage Garden or Duke’s Garden was formed in 1801 when King George III, gave the cottage and land to his son the 2nd Duke of Cambridge. According to the current archivist at Kew the original use of the garden was not recorded as it was built during the Royal period before the gardens became public in 1841. At the time of our visit this walled garden was a profusion of plants from the tropical regions mixed with hardy perennials. Even though walled gardens can provide a microclimate, the London winter weather does require additional protection of the tropical plants in this garden. According to the horticulture Team Leader at Kew who was responsible for the Dukes Garden at the time of our visit, plants such as Dahlia, Bird of Paradise, Umbrella Plant, Elephant Ears and Canna, are dug up in the fall and over wintered in heated glass houses and replanted in May in the garden. The Tasmania Tree Fern and the cold hardy Desert Fan Palm would be left in the garden for the winter and fleeced. Due to colder then usual London winter after our visit where temperatures of 15 degrees F (-9 degrees C) were recorded, these plants were lost. The lilies, such as gingers, calla, and pineapple, are layered with organic mulch for winter protection. Other plants such as Castor Bean, beefsteak, ivies and vines are treated as annuals.

The Grass Garden at Kew was created in 1892 and is a showcase of an example of over 550 species of grasses throughout the world. Grasses are important economically as a food source for humans and animals. Grasses also function to stabilize soil and sand dunes. When used as ornamentals in gardens they provide sculptural interest. A sculpture named ‘A Sower,’ cast by Sir Hamo Thornycroft in 1886, stands as a centerpiece in the garden, his arm outstretched sowing seed where maize and the tall grass Miscanthus sinenis grows. Large groupings of sedums, coneflowers and crocosmia provide patches of color against shades of greens and bronze of the grasses; pennisetums with light, feathery spikes, stipa with bristly feathers and large, dense clusters of cortaderia with plumes of cream colored panicles.

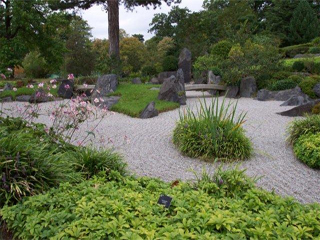

The pagoda, a ten story tapered, ornate octagonal structure designed by Sir William Chambers in 1762 for Princess Augusta, showcases the fascination the British had for the Orient in the 18th century. The Bamboo Garden created in 1891 surrounds the Minka, a Japanese wooden house that country people lived in. It is entirely constructed by materials from plants and nature. Bamboo from China, Japan, Andes and the Himalayas surround the Minka house. A short distance away an ornate structure with a curved roof and elegant carvings of flowers and animals on the exterior panels, is named The Chokushi-Mon or Gateway of the Imperial Messenger.

The Gateway overlooks a formal garden with stone lanterns and dry stone elements representing water movements and mountain regions. Nearby the Garden of Harmony is planted with low-lying hedges of rhododendron, Iris and flowering pink and white Japanese anemone. Planted among the boulders are hydrangea, callicarpa and spiraea bushes. Leaving the Japanese Gardens we took a short tree walk through numerous varieties of oaks and pines to the water lily pond that was a home to a family of coots.

The Arboretum at Kew comprises two-thirds of the gardens and impressed upon this visitor the beauty of trees. Since the founding of Kew Garden, over 14,000 trees have been collected world wide for the arboretum. Sir Joseph Hooker followed the gardenesque style of planting whereby exotic trees were placed to display their individual characteristics to their best advantage. He labeled and arranged plantings in naturalistic groups with an emphasis on botanical accuracy to educate the public. The fledgling trees he methodically placed and planted so they would not crowd each other at maturity now stand individually as impressive works of art. The shapes of the trees, such as the Stone Pine with its umbrella canopy, and the barks of many trees exfoliated with age, exhibit various colors and textures. The Eucalyptus dairympleana (mountain gum) with smooth ivory bark, to smooth streaked colors of tan, rust and charcoaled bark of the Eucalyptus perriniana, (spinning gum) contrast with the dark gray, bulging trunk of the Castanea sativa (sweet chestnut) have over time, created their own sculptural qualities.

Kew states that their mission is “to inspire and deliver science-based plant conservation worldwide, enhancing the quality of life.” In the 21st century Kew is studying the environmental issues facing our planet including the loss of vegetation in many parts of the world to climate change that effects deserts to icecaps. Conservation of rainforests, restoration of habitat devastated by natural disasters and education in African communities to grow and harvest plants important for food and medicine are actively undertaken by Kew’s horticulturist and scientist.

Kew often partners with other botanical gardens throughout the world to achieve mutual goals. An example of this cooperation is the collection and conservation of seeds for the Kew Seed Bank. A “seed walk” was on display with sculptures portraying seeds and pods. The various shaped seeds created by the artist Tom Hare, were woven in willow on light steel frames. The display was in celebration of the Kew Millennium Seed Bank goal of collecting and saving the seeds of 10% of the worlds 300,000 known plants by 2010. The seed bank, with 54 countries contributing to this collection, has set a target to save half of the seeds of known plant species. The 21st century plant hunters are still discovering new species whose seeds are being added to the Kew Seed Bank.

Numerous authors, including Kew’s own archivists, have written the history of the garden and stories of the individuals who guided Kew to its premier status today as an international major botanic garden. David and I had a one-day visit in September to enjoy a microcosm of what Kew currently showcases throughout the year. It was a daytrip with a glimpse of 250 years of a Royal Garden’s history.

Visit this site at: www.kew.org