SWEDEN – NORWAY

June 20th – July 2, 2016

TRAVEL INTRODUCTION

It was on Monday that fellow traveler Lennie Kling and I flew from Norfolk, Virginia on the eastern Atlantic coast of the States into the harbor city of Trondheim, Norway, located in the west central part of the country where the warm Gulf Stream waters of the Norwegian Sea benefit the climate year round. Arriving at the airport in Trondheim on a drizzly Tuesday afternoon we met with George and Dorothy Feather and their friends — Roy Lofts from Halifax and Norah Padgett from Storth, who had flown in from Manchester, England. George had mapped out a 12 day tour to visit the summer gardens of Norway and Sweden which were separated by long distances. It was midsummer in June while we were there; a celebration by the Scandinavian natives for the sun that refuses to give into nightfall.

Roy was the fearless designated driver as well as the meticulous organizer of our luggage that he would pack in tightly at the back of the hired car on a daily basis. He would patiently follow the plodding pace of reindeer commandeering the road in Sweden's Lapland as we traveled from a visit at the Alpine Botanical Garden at Hemavan towards Jokkmok's Botanical Garden. He negotiated the twist and turns of the narrow two lane, well maintained highways of the Norwegian mountains north of the Arctic Circle as we traveled to the “Gateway of the Arctic Circle.” to visit the Tromsø Botanical Garden. Only occasionally did habit cause Roy to have a momentarily lapse and drive on the UK side of the highway.

A two and a half day break from the confines of an automobile came with travels on a Hurtigruten Cruise ship to travel the Norwegian coastal waters from Tromsø down south to Trondheim. This provided a chance for scenic views on the outdoor upper deck of the ship or in the glassed enclosed sitting room that provided a panoramic view of the coastal mountainous region of Norway.

After exiting from the ferry in Trondheim, we again packed ourselves into the Ford seven-seater and headed southwest to conclude the last few days of the trip. It was our first heavy day of rain as we left our overnight lodging in Dovre, Norway. We reached Oslo in the mid-afternoon where Roy's experience of 22 years as a long haul lorry driver was crucial as he maneuvered through the heavy traffic congestion just as the weather began to break. Göteborg, at the end of the day (and 9 ½ hours of travel), was the final destination for Lennie and I. Meanwhile, as a backseat passenger, I had fleetingly taken in the beauty of natural landscapes of birch forests, lakes, fjords and mountain waterfalls we passed in over 1500 miles of highway in Norway and Sweden and a short cross-over into Finland. As a gardener, it had been a fortunate opportunity to visit far northern Scandinavian gardens and the Göteborg Botanical Garden in the southwest of Sweden.

ALPINE BOTANICAL GARDEN IN HEMAVAN, SWEDEN

Visited June 22, 2016

Wednesday morning we left the hotel at Trondheim, Norway and headed Northeast to the mountainous area of Hemavan, Sweden, a short distance past the border with Norway. The alpine garden was not yet open to the public but George had arranged a private tour for us at Sweden's highest (600 meters or 1,968 feet above sea level) and one of world's most northerly botanical gardens. The garden was founded in 1989 by Dr. Olof Rune, based on his visits to the botanical gardens in the European Alps.

Our guide was the manager and superintendent of the garden, Andreas Karlsson, who is also chairman of the 'Friends of the Botanical Garden' that oversees the care and maintenance of the facility. He graciously arranged with George for our visit before the season's open date. He was joined by an enthusiastic team of volunteers whose knowledge (ranging from plants and insects to geology) impressed us.

Being one of the highest gardens, it had a unique arrangement to transport visitors from the entrance to the garden which is at the top of a steep mountain ridge. An elevator inside the Tärna Fjällpark building took us up to the 10th floor where a walkway connected us to paths that surrounded the ridge.

There were pathways through the birch forest but we elected to stay on a well-worn dry foot path in the open where timber boxes covered 31 cultivation areas. Regardless of our choice, swarms of large mosquitoes from the bog found us and swarmed at our faces mercilessly.

From the sunny mountain ridge that faces the valley to the west, Sweden's mountains as well as Norway's can be viewed. A path on that side can be taken through a dry birch forest.

The eastern side of the ridge is shaded and lies next to a long bog. A path runs through the orchid marsh with a wet birch forest above the bog. A different climate of heat and light conditions are created on these two sides of the ridge that was formed by the last ice age. This has provided the opportunity to grow numerous plants from a range of arctic and alpine sites worldwide. At the Hemavan Botanical Garden plant communities are grouped together when possible.

Our guide started our tour where it was shadow and moisture from water running down the hillside. The plants grow taller here as they compete for light. Buttercups from the Ranunculus family which thrive in moist landscapes were in bloom. Our guide looked in vain to show us the small fly that often lives inside the blooms and pollinates the flower.

When Carl Linnaeus toured the Lapland area in 1732, he wrote in his journal of finding the meadow buttercups in Luleå (Sweden) and in Piteå. He stated that they “grow so profusely, making whole fields yellow and quite beautiful to behold.” This buttercup will grow up to 40” and on pasture land the cattle will leave the plant alone as it is poisonous.

The genus Ranunculus has about 400 species of buttercups distributed in temperate regions throughout the world. The Ranunculales aconitifolius (L.) or Bachlor's Buttons, is native to Central Europe, found in moist mountain meadows.

We were given an introduction to wild edibles; the taste of the leaves of the Angelica archangelical, native to Sweden and Norway. Our guide told us that the stems needed to be eaten before the plant flowers. Once it flowers it would be tough like bamboo. Stories of the plant can be found in Scandinavian folklore and numerous references can be found as to how the roots, leaves and seeds of the plant have been used for medicinal purposes.

Linnaeus encountered the Sami use of angelica while in Jokkmokk, (Northern Lapland) Sweden. He wrote of the Sami who “picked and peeled the stalk before the flower had come into bloom; ate it like a turnip as though it were a great delicacy. It really was tasty, the upper and softer parts being particularly good, and the Lapps searched avidly for it.” When he traveled further up into the mountains he wrote that the Sami took the “leaves off with a knife, as were the outer skin, which came off like hemp, and then everyone ate them like apples with great relish.” The leafy sheaths containing the umbels were chopped up and mixed with the sorrel that was being boiled to make sorrel milk. When Linnaeus traveled in Norway he found that the Lapps when short of tobacco would chew the angelica roots in order to have the taste of something strong in their throats.

We moved to the dry birch forest (Boxes 2-6) where the plants are small and compete for water. Exquisite among the mountain rocks was the rare Primula scandinavica. Primula scandinavica is only found in Norway and Sweden. In both countries the habitat of the species and its population is declining. It Norway the decline has been caused by grazing activities that have been abandoned, resulting in overgrowth. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species has labeled the primula as near threatened. In Sweden the reason for the decline is not clear but is labeled as vulnerable and climate change could lead to population declines in the future.

The Silene acaulis (moss campion) with moss like evergreen carpet and tiny pink star flowers, is an example of the short plants that grows in the high mountains of the arctic regions. These plants grow low to the ground for warmth. The leaves will be small so very little of the plants will be exposed to the wind and freezing temperatures found in the Arctic regions. The Silene acaulis rounded cushion shape protects the plant from the cold and drying winds. In Alaska it is recorded that this plant may have reached 300 years in age. The oldest moss campion is 350 years old with a diameter of two feet. At one time the plant was used medicinally for children with colic.

Also in this group were the Arnica angustifolia, (Alpine arnica) unusual in that it grows high above the ground while the other low growing vegetation (stonecrops, saxifrages etc.) are close to the surface. It is often found in crags where it obtains heat and protection from the rocks. In Finland it is listed as endangered and is protected.

Rhodola rosea or golden root, a native plant of Sibera and China, is a stonecrop with bright yellow flowers and succulent leaves that smell like roses when dried. According to folk medicine it had been used as a medicinal plant in China and Tibet as early as 2697 BC. It was in use in Sweden and Russia for centuries when Carl Linnaeus named the plant in 1725 and also documented its medicinal use. Each plant has one gender of flower, either male or female. That requires the help of bees or flies for pollination. The beneficial properties of the plant, according to current literature, lie in extracts from the roots. It has been used in modern psychiatry for its anti-depressant effects. In Russia it has been used for physical and mental performance enhancement effect.

Species that reproduce with spores and are minus colorful flowers (Boxes 7-9) are the club mosses, horsetails and ferns. Grasses with hollow rounded stems and sedges with triangular filled stems are in this group. Sedges can grow in bogs. Linnaeus wrote about this grass (Carex pseudocyperus) in his journal on his Lapland journey. Visiting Jokkmokk he found that the Lapps “put the dried sedge in their boots with the ears still attached to it. They comb it with iron or horn combs and twist it in their hands so that it becomes soft. Then they dry it and put it in their shoes where it protects them against the most extreme cold even if they go without stockings.” In Norway he observed that Lapps wear boots in the winter that reach to the middle of their thigh with no stockings but use the “shoe grass” around their feet.

Snow cover is important for arctic-alpine plants to provide protection from intense frosts. Snow beds form in topographic depressions that accumulate large amounts of snow during the winter months. Late snow beds protect the buds in the wintertime as the final snowmelt does not occur until late in the growing season The snow beds also provide a steady stream of water and nutrients to nearby plant communities. Growing season on the snow beds is short; one to two months. These snow bed plants have special conditions and are vulnerable in a warmer climate.

The area labeled #12 displays low-alpine (lower oroarctic vegetation) heaths that grow in calcareous (lime or chalky and alkaline) soils. It is indicated that they are the most species rich community in the mountains. The Phyllodoce caerulea or Blue Heath, grows high from 2,198-2,755 feet (670-840 meters) in the European Arctic mountain regions, Central and East Asia and North America. It was discovered in the Scottish Highlands in 1810 at the Sow of Atholl. In Great Britain its conservation status there in noted as vulnerable due to a lack of winter snow. In Europe and Scandinavia this evergreen species of shrub that grows to approximately 6” (15cm) tall with clusters of purple flowers is found in abundance, especially in the mountain birch forests.

A tiny beauty that also grows in the high snow bed sites of the Arctic areas of Scandinavia and the cold mountain ranges of the Alps and Pyrenees, is the Ranunculus glacialis, a perennial herb commonly known as Glacier Crowfoot. This little buttercup with a larger than usual bloom for an alpine, grows 2” to 8” (5-20cm) with a flowering time beginning only a few days after the snow has melted. Its seeds will ripen before the short summer ends. It is the world's northern-most flower; in Greenland only 800 miles from the North Pole. The common name is descriptive of the fact that is grows among the glacial rocks. It holds a location record at a height of 14,025 feet (4275 meters) in the Alps and in South Norwegian mountains at a height of 7,775 feet (2370 meters). In Finland it is a protected plant as it is classified as near threatened. From studies the increase in climate heat is already affecting its future as the plants lower limits is rising, possibly as a result of a decrease in snow beds.

Hyperzia selidgo ssp.selago is another high Arctic plant represented in this group. It does not flower because it is to cold. Reproduction is by cloning.

Solorina crocea (L.) has the common name chocolate chip. It is a soil lichen that grows in acidic soil. Chocolate chip is common worldwide and in the Arctic. It is also a snow bed species.

The stones in box #14 come from serpentine rock. Briefly, rocks weather and over time forms soil which is a mineral byproduct of those rocks. Serpentine rock contain heavy metal concentrations of cobalt, nickel and chromium. The resulting soil is poisonous for most plant except for some of the plants in the Caryophyllaceae, Fabaceae, Asteraceae, Poaceae and Ericaceae family. Besides the heavy metals in the soil the plants will also contend with low amounts of calcium and high amounts of magnesium (which inhibit calcium uptake) as well as low levels of nitrogen and poor nitrogen uptake. Organic material is sparse. Still being studied, from the cellular level to the physical characteristics, are the adaptive strategies that have been developed by plants that can tolerate these conditions that most plants cannot.

The Silene acaulis or moss campion (Caryophyllaceae family) and the Rhodola arosea, both pictured previously growing on ordinary soil, also had adapated to serpentine soil and appeared to be thriving in this representative area. Poa alpine vivipara (L) is an alpine bunchgrass (family Poaceae) of the alpine slopes of meadows is another plant represented in this group. Minuartia verna (L.) or spring sandwort (Caryophyllaceae family) is a cushion forming herb that grows on metal rich soils on rocky hillsides. It has even been found growing in calcareous lead mine wastes and on slag heaps. There are plants restricted to serpentine soils only. It was noted at the botanical garden that this rock type constitutes the main part of the mountain range Atoklinten, approximately 25 miles (40 km) from Hemavan.

A collection of plants from the Alps (boxes 18 & 19) and their relatives that could also be found in Sweden's mountains were in their own grouping. The alpine edelweiss, Aster alpinus, Campanula barbata from the Alps and Norway mountains, and Gentiana lutea were grown in this collection but not in bloom yet. We were fortunate though to find in bloom the rare European plant from the Austrian Alps, the Wulfenia carinthiaca with deep violet-blue flowers. The signage at the box stated that it was only known from two different localities, Montenegro and the Austrian Alps.

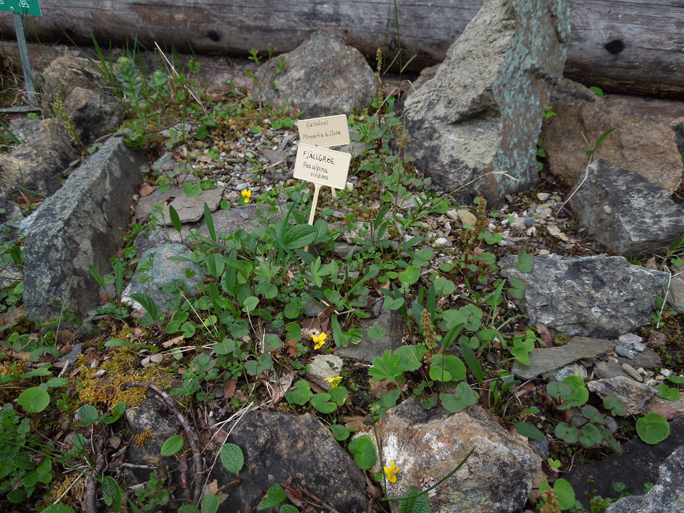

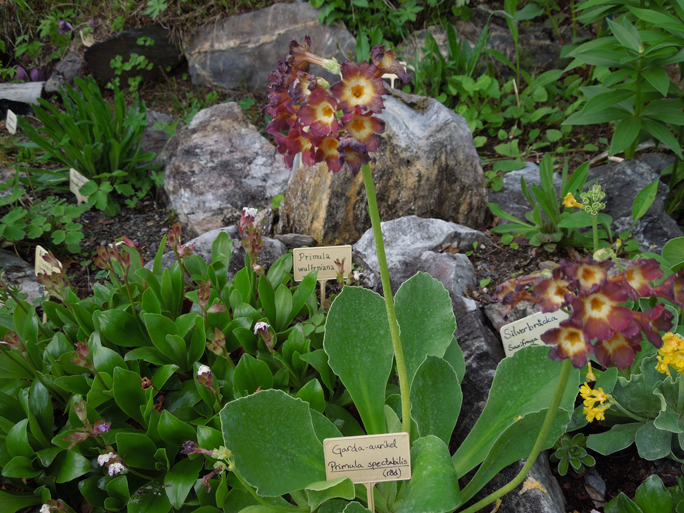

Several varieties of alpine primula were in the mountain group of plants.

The yellow Primula auricula is nicknamed mountain cowslip or bear's ear from the shape of its leaves. Unlike many other primrose, these leaves are thick and waxy and held in a low evergreen rosette. It grows on the rocks in the mountain ranges of central Europe, preferring moist soil and shade. The term auricular is used for plants that have been developed from a hybrid between P. auricular and P. hirsute. As shown by these two photos of primula, the numerous cultivars grow in a wide range of colors.

The Aquilegia alpina (alpine columbine) with nodding blue flowers require gritty, moist, well-draining humus rich soil in cool conditions with full sun. The seeds of the alpine species can take two years to germinate. The signage at the box reminded us that many of the garden plants we have today are refined from the alpine species.

Alpine plants live in their own microclimate. They grow very slowly in extreme habitats above the tree lines in the mountains worldwide. Cold conditions are required. Therefore they contend with low winter and summer temperatures, frost and high winds. Growing seasons are very short. They are sensitive to climate changes, especially increased summer temperatures. The smaller alpine plants do not compete well with the taller and more rapidly growing grasses and small shrubs that are moving upwards from the lower fields due to changes in precipitation and temperature which affect the.snow-lie areas. Recent studies of the plants in the Swiss Alps showed that it was not only higher temperatures that affected the alpine plants. A key factor was the migration of these larger plants that negatively affected the performance and survival rate of the alpines, which should be included when forcasting responses to climate change. Climate change is affecting alpine plants but the studies indicate that the reasons are more complex than a singular response to temperature increase.

Travel Reflections

After leaving the Hemavan Botanical Garden we traveled a short distance to the Tärnaby Fjällhotell for our evening stay. It was a leisurely dinner with a menu that included fish and moose-reindeer stew with potatoes. Familiar to me was the after dinner treat of sorbet with a touch of champagne in the bottom of the glass. An impressive scenic view directly outside the window was Lake Gäuton with reflections of distant snowcapped mountains in the still waters. Later in the evening, around 10:30 p.m. I took a short walk to get photos of the lake. We were at where the sun does not set for the day.

Thursday morning (June 23rd) we headed for Jokkmok, Sweden. Roy had his method for the daily packing of our luggage in the rear of the vehicle. By the time we left the 'Trollifjord' cruise ferry on the last week of our trip, Roy would have the luggage packed in before the 5 of us would be belted into our seats. It was a tight fit.

On the roadway in Sweden's Lapland Mountains, the reindeer have “The Right-Of-Way.” Patience Roy!

Reindeers could be seen grazing along the highway or in the woods where they eat willow and birch leaves and sedge and grass. In the wintertime they will dig down into the snow with their sharp winter hooves to reach on the ground “reindeer moss,” which are lichens of the Cladonia family, C. Stellarus and C. Rangiferina.

Our tour leaders George and Dorothy, along the railroad line that services the Inlandsbanan Railway. We stopped to eat lunch at the small eatery and museum in the old station building at Moskosel, one of the stops on the line if you travel the country by rail.

The Arctic Circle is the southernmost latitude where the midnight sun can be seen at the summer solstice. We reached the marking for the Arctic Circle early Thursday afternoon. Lennie, Deborah & Norah (left to right) sat for an Arctic Circle photo. Late afternoon we reached our next destination, Jokkmokk, Sweden.

Photos by:

Deborah Ellen McMillin

References:

Linneaus, Carl, “The Lapland Journey,” “Iter Lapponicum 1732” Edited and Translated by Peter Graves, Lockharton Press, Edinburg 1995.