When George Feather scheduled a June 2014 trip for Sweden for Lakeland Horticulture Society Members, it was the chance to visit the gardens in the country of my great grandfather from Halland and my great grandmother from Kristianstad. “Land of my ancestors,” I told George, and signed on. Fellow Virginia Beach Master Gardener, Lennie Kling, joined me for the two-week trip that we traveled with thirteen members of the LHS from England. Our trip took us from Uppsala on the mainland to the Island of Gotland and ending in Stockholm. I will cover highlights of what was a fast paced garden tour of private and public gardens with several nature reserves included.

Uppsala and the Linnaeus Garden

The beginning of our tour was in Uppsala located 44 miles North of Stockholm. The countries oldest cathedral and university (founded in 1477) are in Uppsala. In 1702 three quarters of the medieval city was destroyed by fire seriously damaging what was then the Uppsala University Botanical garden just a short distance from the Fyris River that flows through the middle of the city. Under Carl Linnaeus’s tenure as professor of medicine at Uppsala University, from 1741 until his death in 1778, the botanical garden was restored. In 1802 the garden was closed and moved to the grounds of the Uppsala Castle. Cold winds, frost, lack sufficient sunlight and flooding from the Fyris River necessitated the move. In 1923 the original garden was restored, reopened and renamed the Linnaeus Garden.

For gardeners and botanist world wide, Uppsala is known for it association with Carl Linnaeus who was the 18th century Swedish physician and botanist credited with creating order out of the unwieldy and lengthy descriptive identification of naming of plants and animals. He created a classification system, ( based on the work of other seventeenth century scientist), incorporating the categories of kingdom, class, order, genus and species. He based his system on the characteristics of a plants sexual organ according to the number, size and arrangement of their pollen bearing stamens, (24 classes identified) and divided these into orders according to the number of their pistils at the center of the flower. It was his use of binomial nomenclature in his long comprehensive works that eventually became acceptable by botanist and zoologist when they found it indispensable.

Modern techniques of DNA-sequencing may call for changes in the organization and naming of plants based on their genes rather then their appearance. But currently, the consistent binomial system where the first Latin name indicates the genus and the second the species, still stands and is used today universally for plants and animals.

The inspiration for Carl Linnaeus’s name was the lime (linden) trees that grew on his father’s estate in Småland. Currently a pair of massive lime trees that were planted in the 19th century in honor of Linnaeus, flank the original gate at the entrance of the Linnaeus Garden located in the center of the city. An additional six lime trees, impressive in their girth and beauty shade the Forecourt.

Corey, the garden curator, was our guide to this restored historical garden with approximately 1300 species that had originally been cultivated by Linnaeus, now laid out in the French style of the original academic botanic garden of the Uppsala University. As Professor of Medicine, Olf Rudbeck the Elder established the botanic garden in the center of the city in 1655. The Uppsula fire of 1702 seriously damaged the garden and due to lack of funds, it was abandoned for 40 years.

Linnaeus tenure as Professor of Medicine came with the responsibility to manage the Botanical Garden. Linnaeus restored the damaged garden for educational and teaching purposes. With over 3,000 species of plants he laid out his garden bed parterres according to seasons and his sexual classification of plants.

A gravel pathway down the central two thirds of the garden is lined with ornamental plants grown in the Uppsala area in the 1700’s. The daylily, phlox and peony in bloom at the time of our visit, were new novelties at that time as Corey explained that many of the new plants that were sought out by Linnaeus came to his garden from his disciples and contacts who traveled Siberia, North America and other parts of the world. Catherine II of Russia sent him seeds from her country as his reputation spread to other parts of the world.

Centered in the garden is a statue of Venus, (scandalous at the time since naked), which Linnaeus placed in front of the star shaped Lake Pond featuring white water lilies. To the left is the river pond with royal ferns and purple Iris and to the right the marsh pond, where Linnaeus’s preferred flower, the twinflower, Linnaea borealis is currently grown.

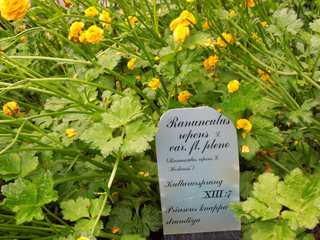

In the Perennial Parterre the species are planted according to the 24 classes in Linnaeus sexual system. The perennial beds are native plants and other species from the northern regions of North American and Europe. The Annual Parterre (including biennial plants) consists of 44 beds. Linnaeus instructed that all the beds in the parterres are narrow enough so that one person walking along them could weed them. The hedges surrounding these two areas are a mixture for Linnaeus’s educational purposes; mock orange, barberry, willow and spruce.

The Spring Parterre has plants from Siberia, which Linnaeus would cover in the wintertime to protect from the cold since they would start early spring development. Linnaeus noted that the spring flowering bulbs of Crocus, snowdrops and spring snowflake would begin blooming on the same day that the wagtails would return and the frogs would begin croaking.

The autumn Parterre has many species from eastern North America and in 1745 Linnaeus wrote “we owe a considerable number of these to the Virginian soils.” A native species from Virginia is the coneflower Rudbeckia laciniata, named by Linnaeus after Olof Rudbeck and his son, Olof the Younger. The Colchium autumnale would be the last to bloom in the autumn garden shortly before the August frost and served as a reminder to Linnaeus to take the “Indian”(Virginia) plants indoors.

At the far end of the garden is the hot house or Orangery that was originally built in 1744 with three heated rooms but in the early 19th century was converted and modified for other uses. Linnaeus had referred to the Orangery as “the soul of the garden, without which no academic garden can survive.”

As we stood outside the Orangery in the Southern Parterre (that Corey called the Mediterranean Garden), he explained that the Orangery was divided into three sections named after the divisions in Roman baths. Plants, which spent the summer on the gravel ground in front of the Orangery were kept in the coolest section during the winter, the Frigidarium. Tropical plants would be moved to the Caldarium, which was warm and humid. Tepidarium was the hot, dry department where succulents and plants from South Africa were grown.

The beautiful Bay Laurels in huge pots are moved indoors in the wintertime. Also in the Mediterranean Garden in pots are a fig tree from South Arabia, Pomegranate tree which Linaeus called the “apple of Carthage,” apricots from Siberia and Manchuria and a peach tree.

The garden was also a zoological garden. From South America Carl Linnaeus had apes, various parrots and birds as well as hedgehogs and Guinea pigs. From Africa there were parrots and Guinea fowl. A pet raccoon entertained children. Throughout the garden there are tall poles with monkey huts placed on the top for his cotton- topped tamarin, a monkey from Columbia, South America that weighed less then .5 kg. The money was a gift to Linnaeus from the Royal Family.

Linnaeus Museum

Our tour of the garden was not complete without a visit to the Linnaeus Museum, the Linnaeus’s family home for thirty- five years. It was not only a residence that was provided to house the professor and his family during his tenure, but also where Linnaeus would lecture students, conduct scientific research and write.

Olof Rudbeck the Elder had originally built the house in the 1690’s, for his son (the Younger) who had taken over his father’s professorship of medicine. The home survived the major fire of Uppsala in 1702, as the Elder, who was also an architect, had the foresight to use fireproof materials in its construction. Extensive renovations were commissioned by Linnaeus to modify the house to accommodate family living area on the ground floor and the upper floors for his library, studies, teaching and scientific displays. A studio in the home provided Linnaeus with a view of the garden, which was “his classroom, his botanical dictionary and his joy.”

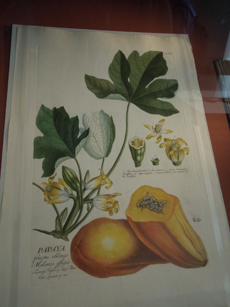

In 1735, George Clifford, a wealthy Anglo-Dutch merchant, employed Linnaeus to describe all of the living and dried plant material at his Holland summer estate of Hartekamp. The catalogue, (2 years in the making) with its use of binominal names, was the forerunner to his Species Plantarum, (1753) which was the starting point for the Latin binomial name of plants. The library upstairs houses a glass cabinet where Linnaeus catalogue of 1737, “Hortus Cliffortianus,” is laid open displaying detailed botanical drawings which were done by George Dionysius Ehret and Jan Wanderlaar.

It is said that he was a popular speaker and in the lecture room his students would gather around the table (for a fee) to hear his talks and observe his demonstrations. An additional room displays the natural history collections of insects, minerals and seashells he organized and published as a catalogue for the Swedish Queen Lovisa Ulrika and his medicinal collection.

During 1932 Carl Linnaeus had traveled five months alone on a scientific expedition to Lapland (Northern Sweden) where he found in the woodlands a small semi-woody evergreen plant with nodding bell shaped light pink flowers born in pairs. The “sugar candy” fragrant blooms last about seven days. Linnaeus had a strong ego (has been called “confident to the point of arrogance but charming enough to compensate.”), but he himself did not give in to naming plants after himself. It was his friend Frederick Gronovious, who in honor of Linnaeus named the plant from the northern regions, Linnaea borealis or twinflower.

The twinflower was Linnaeus “charm” and an often-used motif throughout his life. He wrote of it, “A plant in Lapland, short, overlooked and disregarded with only a brief time in bloom. The plant is named for Linnaeus, who is like it.” When he proposed to Sara Elisabeth Moraea he wore his Lapland peasant wear. A painting in the museum shows him dressed in this garb and between his fingers he lightly holds this delicate flower. His wedding portrait also shows him with the twinflower held gently through his fingers.

The china room in the museum displays the porcelain china service decorated with the Linnaea borealis flower, that Linnaeus obtained through the Swedish East India trading company. The first set that he received in 1752 was not to his satisfaction as the flowers were red rather then pink.

A new set was ordered from China with a template illustration from his own work, the Flora Svecica sent to the craftsman. He was never successful in growing the twinflower in the garden so he grew it in flowerpots. The twinflower is now the floral emblem of the province of Småland where Carl Linnaeus was born in 1707.

Hammarby – The Family Summer Home

By 1758, Carl Linnaeus had been granted nobility by the Swedish King Adolf Frederick and took the name Carl von Linné. He was established as a scientist and was a popular professor at the Uppsala University often taking his students on festive picnic trips into the countryside in the summertime in search for rare plants, a bugle blowing when one was found. He was concerned though as to his family’s future since the residence at the University Botanic garden was provided for the professors during their tenure only. He wanted to get his family away from the unhealthy city where two of his children had died from disease when young. He saw the countryside and its nature as where everything is green and beautiful; you can be refreshed by it and find God. It was the countryside southeast of Uppsala where he bought the small summer estate of Hammarby, which means rocky or stony hill.

The estate house faces pasture and horse farms, all part of the property that was once crown lands used for hunting by the kings. In the 18th century it made Linnaeus a wealthy landowner when he purchased the additional farmland. Stables, cowsheds, sheep barn and henhouse are a part of the estate. In Linnaeus’s day there was a kitchen garden to provide vegetables for the family. Timber fencing encloses an orderly vegetable and herb garden in use today.

The woodland behind the home is strewn with large moss covered boulders. Running wild as a ground cover on the forest floor, the Mercurialis perennis ( dog’s mercury) cultivated by Linnaeus as an example of the sexual nature of plants since it is a dioecious, (male and female flowers on separate plants) species. The plant is pictured along side Linnaeus on the Swedish hundred kroner note.

A French style garden is at the front entrance of the property. Apparently Linnaeus did not write much about the estate except the flowerbeds that he did have in the front of the house. Linnaeus brought approximately 800 plants to Hammarby continuing summer lectures with foreign students from four separate continents.

The visit to this home reflects his private life. Personal items shown including his skullcap to relieve migraines, his tobacco pipe and the family wardrobe are examples of daily life at that time. Financially he was not able to publish lavish illustrated botanical books. Instead he received prints and hand colored engravings from the paintings of artist and friend, Georg Dionysius Ehret. He wallpapered his bedroom and studio with these prints and floral images cut out from books. Now century’s aged, they are still plastered to the walls where the portraits of his four daughters, his son and pet monkey hang.

On the rocky hillside behind the residence I found the Linnaeus History Museum, a small one room building Linnaeus had built of stone to resist fire. Uppsala had a second major fire in 1766, which had come close to his home. Linnaues was reminded of the fire of 1702 in which Olof Rudbeck the Elder had lost his herbarium collection and flora project. He decided that his natural history collections were no longer safe in the city. Looking through the doorway into the room was a table with a listing of his collections he brought here; mineral, insects, shells, fossils and a herbarium cabinet. He often lectured his students in the summertime outside his fireproof building in the woodland clearing which was a safe distance from his house.

His massive collection of specimens, letters and books was sold in 1783 by Linnaeus’s widow to a young English medical student, James Edward Smith and shipped to London. Smith founded the Linnean Society of London to preserve the complete collection. The collection is available to scholars and researchers at the society’s headquarters at Burlington House.

Linnaeus, who had stated, “God created – Linnaeus ordered,” suffered from depression and pessimism in his later years. Debilitating illness; malaria and later angina and sciatica from the hip to the knee, then a stroke in 1774 that left him partially paralyzed for a period of time, clouded his memory. Over the next three years his health continued to deteriorate.

As a young boy he had worked with his father in the rectory garden and as early as age five, he memorized the lengthy names of plants. In his last year of his life the “great biological name giver,” could not recall a single name of the 8,000 plants he had named or recognize his own writings. After a severe seizure he died January 10th, 1778 at his home in Uppsala.

A stately funeral was held for Carl von Linné at the Cathedral of Uppsala. Large crowds lined the street while the church bell tolled. His ashes now lie under a flat stone near the entrance door of the Cathedral of Uppsala. He had left instructions that nearby there should be a bronze medallion inscribed with his name, date of birth and death and the words Princeps Botanicorum or Prince of Botanist.

Credits

Photos by Deborah McMillin

Linnaeus’s wallpaper from Linnaeus’ Hammarby, National Properties Board Sweden brochure.

Group photo was taken at the Ersta Terass restaurant on Södermalm (Stockholm) by the waiter and includes our coach driver for the majority of the trip, Daniel.

Berglund, Karin, “The Linnaean Legacy,” The Linnaean Special Issue #8

The Linnean Society of London http://www.linnean.org

Quammen, David, “A Passion for Order,” The National Geographic Magazine June 2007

Stjernström, Peter, Young Man Turns 300, About Linnaeus 2007, Nygren & Nygren 2009